The international and student exhibitions at the Prague Quadrennial belong to a niche when discussing genres of art. Even in Europe, where spatial installations are a little more prevalent than in the United States, the idea of conceptually creating a space to be experienced in a museum setting is still not main-stream. Anyone in the general population knows what it is to look at a painting, or a photograph, or a sculpture. It takes a little more effort to communicate the concept of this sort of art.

Those who are familiar with the art form, however, might be prepared to compare different exhibits. Some are more interactive than others. Each flows in its own way. Some are designed to shock. Others soothe.

Some factors are much more poignant than mood, though. One of the most critical aspects of a spatial installation is a set of choices I am going to call modality.

Modality refers to the specific mode of experience that a given installation aspires to. There are a great many things that these works do, all of them deriving from the choices made by the designers. I think it is fair to say that every exhibit in both the professional and student exhibitions are, in some way, striving to convey theatricality. From there, each takes its own path in how it interacts with the human participants happening upon it.

I wish that I had the time to write about every work present at the Clam-Gallas Palace, the Church of St. Anne, and at Kafka’s House. These three sites house the various professional and student exhibits designed and built by artists all over the world. Forgive me for neglecting to mention a great many brilliantly designed works.

Getting back to modality, an important choice is whether participants are dealt with as a community, or as individuals. This is a big choice to make. It would be fair to write that it defines opposite ends of a spectrum for the exhibits.

For starters, consider Make/Believe, the professional exhibit from the United Kingdom. It represents the work of twenty-two designers, emphasizing the identity of the United Kingdom, alongside the passage of time. It is a looping media stream, projection-mapped on three walls of a white room. Benches and pillows are placed centered in the space, encouraging passers-through to sit and experience the deluge of imagery. It is continuously changing, striking and beautiful.

It is impossible for anyone to pass through the room without casting their own shadow into the mix of images. The effect is that there is always a small audience gathered in the middle of the room, thoughtfully processing the imagery, while individuals quietly slip in and out of both the room and the projections. More than any other exhibit, I believe that this one unites the participants together as a theatrical audience, and encourages contemplative, yet also very passive observation from the group.

In sharp contrast to Make/Believe, we have the exhibit from Canada titled Shared [Private] Space. A row of outhouses is wrapped around the exhibition space. A specific production design is showcased inside each one.

In order to examine the individual designs, participants must enter the outhouses, and close the door behind them. Now, the participant is completely alone with the work being examined. The work displayed inside the outhouse included props, models, video-media with headphones, renderings, and more.

I personally found that I was more engaged with the art when I was experiencing it as an individual, rather than as a member of a crowd. I am well aware that we do not all experience things like this in the same way. It is worth noting, too, that the doors did not lock, and it was impossible to know if a given outhouse was occupied. While engaged with a given show, it was common to have other people walk in on you, apologize, and then close the door.

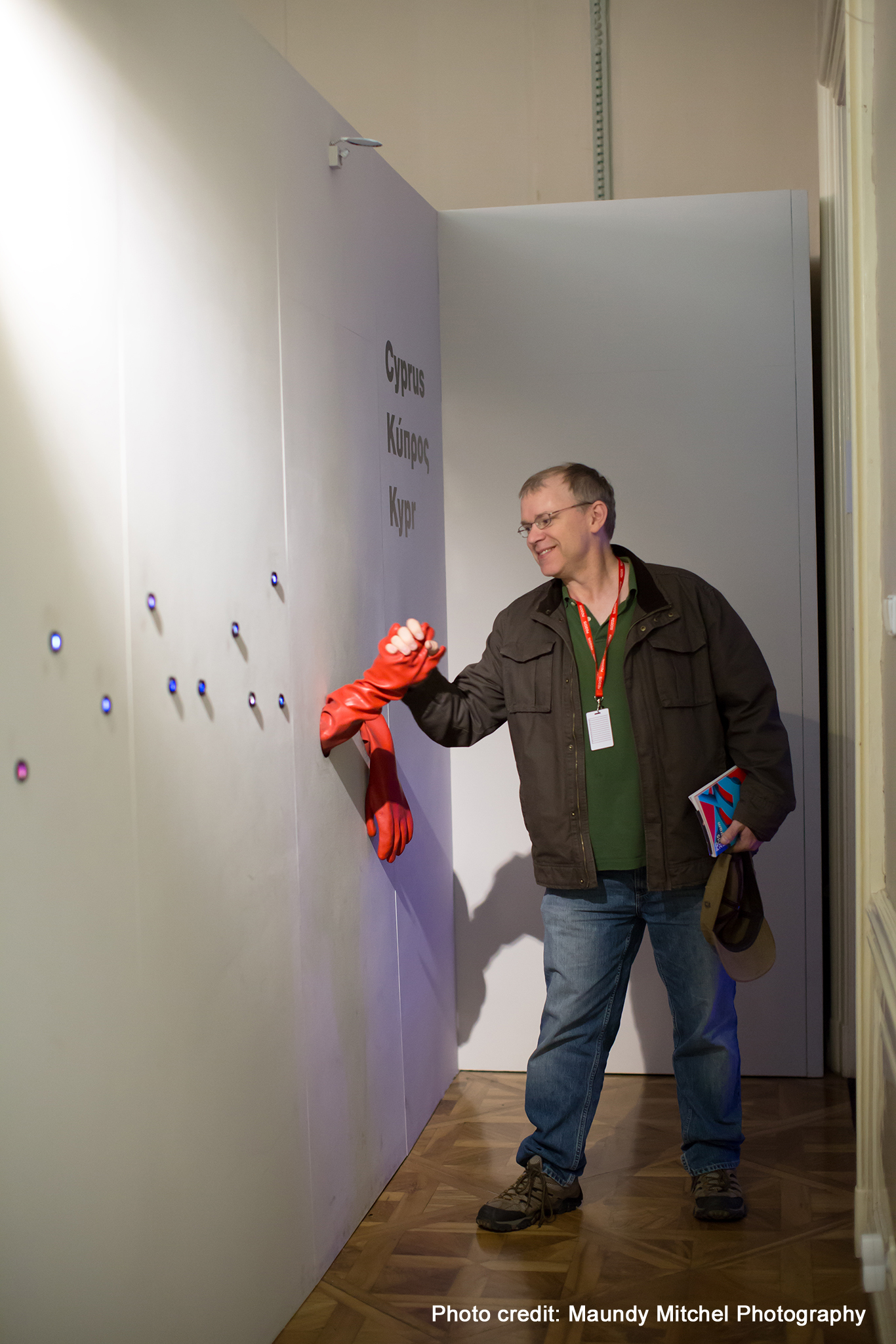

Another exhibit that isolates participants is Creatures, designed by Elena Katsouri and Georgios Koukoumas for Cyprus. I know from discussions with Georgios that a part of the intention was to examine the fact that fewer people are attending the theatre in general. I believe there is an almost satirical statement in play by designing an exhibit where participants view aspects of the exhibit completely alone.

The exhibit has a prominent front area with beautifully designed creature-costumes on display. It includes a sort of side-alley, dotted with tiny peepholes. Each peephole allows the peeper to see an image from a single show. The peepholes wrap around to the back of the exhibit, leading to a mysterious set of rubber hands hanging from the back.

Also in the front of the exhibit is small door, leading to a pitch-black interior. Various interactive scenic models with lights and noisemakers are spread throughout the interior, and other artifacts to be examined. It is difficult to see or navigate inside, so each participant is issued a small flashlight as they enter. Again, this serves to keep every person isolated and experiencing the exhibit very much on their own.

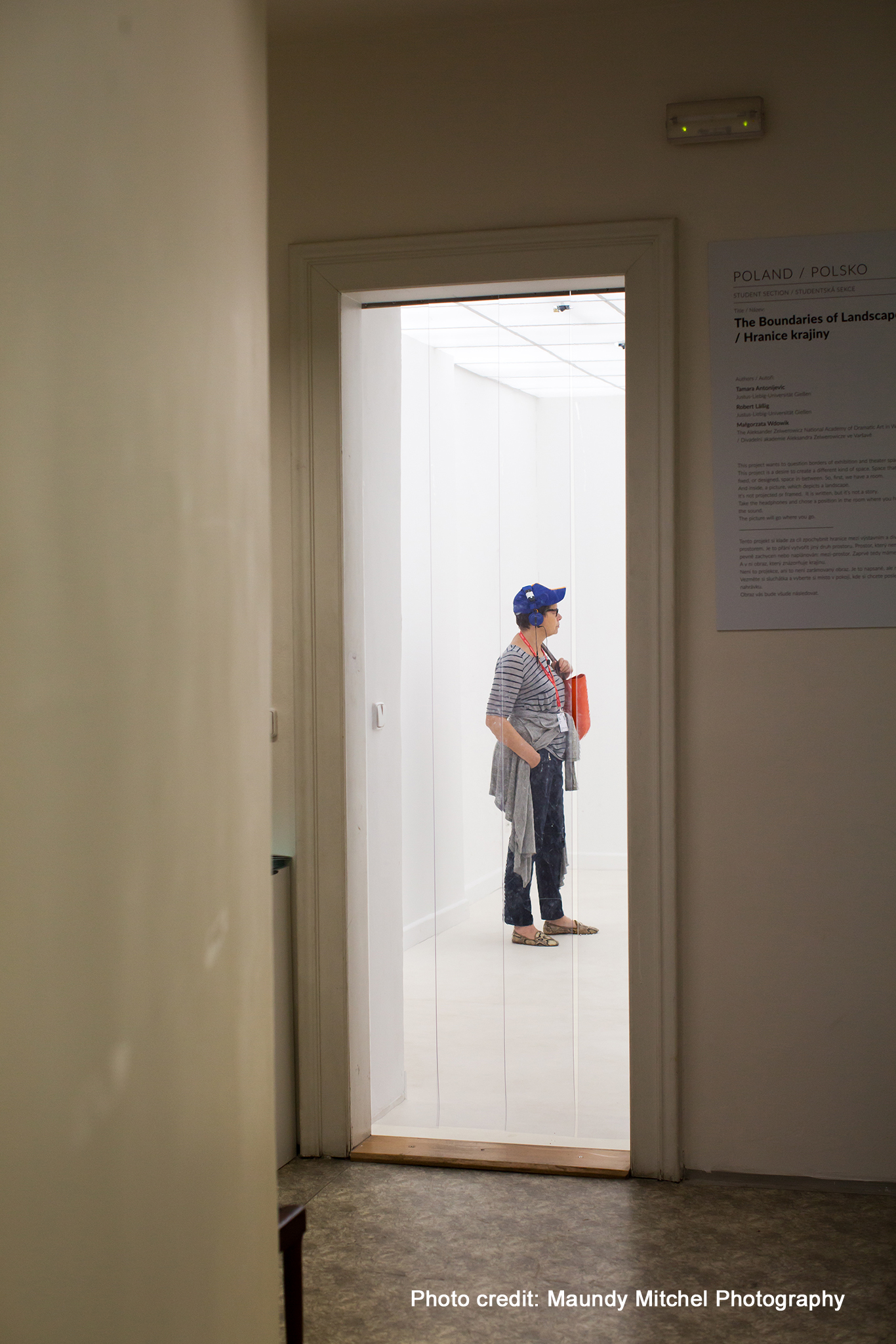

One of the most unique applications of modality that I observed among all exhibits, however, was in the student exhibits at Kafka’s House, just off of Old Town Square. The Boundaries of Landscape was both designed and engineered by Tamara Antonijevic, Robert Lassig, and Matgorzata Wdowik on behalf of Poland.

I had walked past this exhibit initially thinking it was not yet installed. The exhibit is an empty white room. It is really, really white, and really empty. The ceiling is a grid of diffuse white light. When I was passing the exhibit on my way out of that part of Kafka’s house, Matgorzata offered me a colored hat, a set of headphones, and a computer tablet. She wanted me to go into the empty room while wearing these things. I didn’t know what to expect, but at the PQ, you just jump into things.

I walked into the room. A recorded voice began describing a painting that was forming on the wall. It told me about the sky being rendered, and the expansion of a particular shade of blue. I looked around the room, expecting to see a projection appearing on one of the walls. Nothing was happening. Two other people were standing, staring blankly into space, also wearing hats and headphones. Was this exhibit broken? Nothing was happening. I took two steps back towards the door, and the voice began again. Now it was addressing all of us. It spoke of those of us who were staring blankly at the floor, avoiding eye-contact with the others. It spoke of those who were staring at the walls, imagining what was being described to them. It spoke of those looking around at the other participants. I looked to those other people at that moment, expecting to share a knowing glance. They were not looking at me at all. They were not listening to the same thing that I was hearing. They were one their own in here, just like me.

Throughout the room, various points are defined, and automatically play specific recordings for participants. I found that I needed to move very slowly and carefully, finding the key spots where I could experience the different parts of this invisible museum. Everyone in the room with me was experiencing the same thing, yet none of us were experiencing it together. We were together, and we were alone. The room is both an amazing piece of theatre, as well as a museum.

This exhibit fulfills multiple, normally contradictory possibilities for a spatial installation, and it does this with a completely empty room.

From me to you, Tamara Antonijevic, Robert Lassig, and Matgorzata Wdowik: Bravo.